The Great Barefoot Running Hysteria of 2010

03/25/25 • 9 minute read

The year was 2010. Ke$ha's “Tik Tok” was topping the Billboard charts. Steve Jobs has just introduced a goofy new oversized iPhone called an “iPad”. And in running forums across the internet far and wide, hoards of enthusiasts preached the gospel of a new way of running: without shoes.

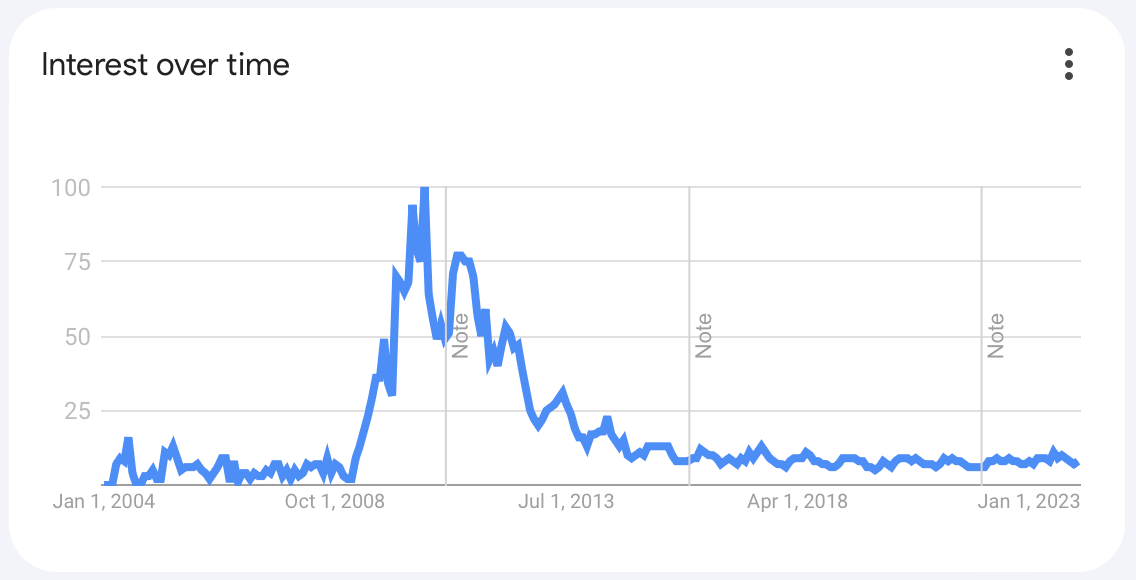

The “Great Barefoot Running Hysteria of 2010”, as I call it, took the amateur running world by storm. Propelled by dramatic claims of performance improvements and injury prevention, barefoot running gave rise to a vocal (and often militant) contingent of enthusiasts and entirely new classes of footwear. And then over the course of a several years, it faded away almost as quickly as it came, leaving behind changes in running shoes and culture forever. In this post, we'll explore the history and legacy of the barefoot running movement.

The Barefoot Running Movement & How It Started

Barefoot running is–of course–as old as humanity itself. In fact, people have run barefoot throughout most of human history, with the practice continuing today in several cultures, such as Kenya and indigenous peoples in Mexico.

In this sense, before addressing the modern origins of barefoot running, we need to talk about the origins of shod running. The concept of running shoes as we understand them today, specifically designed to improve running efficiency and comfort, did not emerge until the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This evolution coincided with the rise of organized sports and recreational running, which spurred the development of footwear tailored to the specific needs of runners.

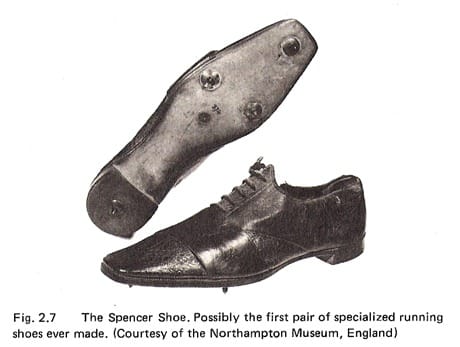

The first breakthrough came in 1865 when an English shoemaker brilliantly suggested adding spikes to otherwise normal-looking dress shoes to make them suitable for cross-country running. Later, in the early 20th century, shoes with rubber soles were introduced, offering improved grip and shock absorption, marking a significant advancement in the design of running shoes.

The result of these running shoe trends was running shoe stores filled with bulky, over-engineered clown shoes that promised to prevent running injuries, but probably didn't.

Into more modern times, running shoes continued to evolve past their humble beginnings into heavier, more complex footwear with exotic materials like plastics & EVA foam. In the 80s and 90s, many shoemakers became fixated on stability and the notion that pronation, the natural roll of the foot after it lands, was a cause for running injuries. Running shoes were increasingly designed to try to prevent this movement with wedges of foam that support and stabilize the arch of the foot, a high heel-to-toe drop, and other questionable features like plastic air bubbles in the heel to cushion the foot with each step.

The result of these running shoe trends was running shoe stores filled with bulky, over-engineered clown shoes that promised to prevent running injuries, but probably didn't, and were mostly just uncomfortable to use. You can see an example of this kind of design in action in the Nike Air Max 90, which is now also available in a more tasteful re-issue. While the original was marketed as a running shoe, the modern re-issue is a nostalgic fashion shoe that you should definitely not run in.

The barefoot running renaissance can thus be understood as a backlash to the dominant running shoe trends at the time. The revival was driven by a growing dissatisfaction with traditional running shoes, which many believed contributed to injuries and impeded natural foot movement. Proponents of barefoot running argued that it encouraged a more natural gait, reducing the impact on the legs and back and enhancing the overall running experience.

In 2004, inspired by Stanford athletes training barefoot, Nike introduced the Nike Free, a running shoe that bucked the bulky running shoe trends of the time with a super flexible sole and a minimal heel-to-toe offset.

Then, in 2006, Vibram launched the 5-Fingers: a shoe intended to be as close to barefoot as possible, with a thin rubber sole and glove-like fit for the toes. This was the shoe that truly ushered in the minimalist mindset: running shoes should enable a "natural" gait and that less is more.

The barefoot-inspired Nike Free and Vibram 5 Fingers set the stage, but the real barefoot running revolution began not with a pair of shoes, but with a book about an indigenous tribe of Native Mexicans.

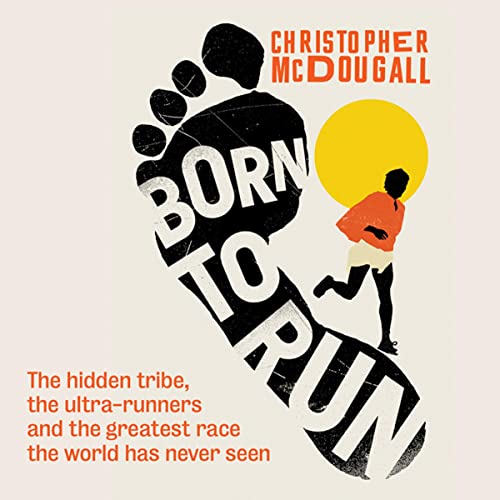

Christopher McDougall's "Born to Run"

While the over-engineered running shoe backlash had already started with shoes like the Nike Free and the Vibram 5 Fingers, the spark that lit the barefoot running powder keg was Christopher McDougall's 2009 bestseller, "Born to Run". The book, which explores the running habits of the Tarahumara Native Mexican tribe, known for their long-distance running ability, captivated the imagination of runners–and non-runners–everywhere.

The Tarahumara, or Rarámuri, as they refer to themselves, are an indigenous people who reside in the rugged and remote Copper Canyon region of Northwestern Mexico. Renowned for their extraordinary long-distance running abilities, the Tarahumara have garnered international attention and admiration from runners and researchers alike. Their running habits, deeply embedded in their culture and lifestyle, are not merely for sport but serve practical and ceremonial purposes as well.

McDougall's narrative suggested that modern running injuries were virtually non-existent among the Tarahumara. They often ran barefoot or in minimal footwear, sandals crafted from leather and tire strips called huaraches. The sandals provide minimal cushioning and protection, promoting a natural running form that many attribute to their low incidence of running-related injuries according to McDougall.

The popularity of McDougall's book sparked widespread curiosity and enthusiasm for barefoot running, and many readers happily ditched their bulky running shoes for new, minimalist alternatives. As the barefoot running movement evolved, so did the market for running footwear, leading to the development of minimalist shoes designed to mimic the barefoot running experience while providing some protection from the hazards of rough terrain.

The Influx of (Mostly Newbie) Barefoot Runners

Bolstered by the popularity of "Born to Run", barefoot running was suddenly everywhere. This period saw a surge in barefoot running clinics, forums, and social media groups where enthusiasts shared tips and experiences.

And as often happens, what started as a perfectly reasonable idea took on a life of its own and became dogmatic: barefoot running was the way to run. The movement gave rise to a series of increasingly lofty and strongly worded claims: barefoot running prevented injuries; barefoot running was more efficient; heel striking was evil; barefoot running was the natural and therefore "correct" way to run. The idea transcended running communities and seeped into popular culture prompting lofty headlines like this New York Times article, The Once and Future Way to Run.

The idea even transcended the sport of running itself. To many, the barefoot running movement was not merely about the act of running without shoes; it represented a broader philosophy seeking to embrace simplicity, natural form, and mindfulness in the pursuit of physical fitness and well-being. The fervor around barefoot running bordered on religious.

Despite the smug sense of superiority that some barefoot proponents projected, many of the most enthusiastic adopters of barefoot running were, in fact, novice and inexperienced runners. While barefoot running enthusiasts were eager to point out elite runners training or racing barefoot, like Zola Budd, these barefoot elites are the exception rather than the rule. Most serious and elite runners generally sat out the barefoot trend, or at least took a more nuanced approach. Many advanced runners already gravitated towards less bulky shoes, and many that did adopt barefoot running did so as part of isolated workouts on soft surfaces.

It's difficult to quantify this claim, but my personal memory of this period was that online discourse around running form and footwear was dominated by an aggressive mob mentality around barefoot running. If you were running with shoes on, you were–according to the online mob–"doin' it wrong", as the internet was fond of saying at the time.

Though it generally didn't represent the opinions of more experienced runners, the barefoot running crowd was certainly the loudest. Opinions that didn't completely jive with the all-minimalist approach were often brutally and violently downvoted.

The Backlash and The Downfall of Barefoot Running

Despite the enthusiasm and claims of the benefits of barefoot running, research into the practice was thin. While some of the claims seemed logical, most of the evidence around the benefits of barefoot running was anecdotal. Much of the argument hinged around barefoot running being the natural and thus correct way to run, and that running with over-engineered running shoes was unnatural and thus incorrect.

Some will recognize this line of reasoning as the appeal to nature fallacy: a logical fallacy in which a subject is claimed to be good simply because it is natural. The fallacy pops up frequently in health & medical settings when people extol the virtues of "all-natural" products or alternative medicines. Sure, some natural products are healthy and beneficial; but so are a lot of deadly poisons. Similarly, diet, where the appeal to nature is used to justify all sorts of sometimes conflicting food choices (throughout history humans have eaten wildly versatile diets). This doesn't mean that natural is bad, it simply means that it's not a valid argument in and of itself for the benefits of barefoot running.

As time went on and the research caught up with the trend, the results were mixed at best: some studies showed potential benefits, while others highlighted increased risks. Critics of barefoot running point to evidence showing an increased incidence of certain types of injuries, such as Achilles tendinitis and metatarsal stress fractures, among runners transitioning to barefoot or minimalist running without proper adaptation. Additionally, there's an obvious concern about the lack of protection from environmental hazards (e.g., sharp objects, rough terrain) when running without traditional footwear, which can lead to acute injuries.

At the same time, many fledgling barefoot runners soon faced a reality check. Reports of injuries began to surface, casting doubt on the benefits of running without shoes. Podiatrists and sports medicine professionals started warning about the potential risks, especially for those with pre-existing foot conditions, those who transitioned too quickly, or those who tried to run too much.

Many who stuck with the sport and aspired to run longer distances such as the marathon soon learned that it's simply difficult to put in the mileage required to excel at these distances without proper footwear. Though you're sure to find counterexamples (I still see a small handful of barefoot runners at major running events like the Boston Marathon), most runners who are putting in 50, 60, 70, or more miles a week to race a marathon are doing so with shoes designed to help cushion the impact.

Long-Lasting Changes to Running Shoes

Despite the decline in barefoot running's popularity, its impact on the running shoe industry was undeniable. Recognizing the demand for a more natural running experience, shoe manufacturers began developing more lightweight, minimalist running shoes with less cushioning and a lower heel-to-toe drop.

More importantly, the minimalist movement helped end the dominance of needlessly overbuilt running shoes. Of course, highly supportive & motion control running shoes are still available, and some runners prefer to run in them, but it's no longer the dominant paradigm.

Ironically, the minimalist shoe movement triggered its own backlash with the maximalist shoe movement of mega-cushioned shoes, ushered in by brands like HOKA. But the maximalist trend is not a return to the overbuilt shoes of the 90s–in fact, it still incorporates minimalist concepts like lower heel-to-toe drop, lightweight materials, and placing less emphasis on the support and motion control that earlier running shoes relied on.

These innovations aimed to combine the benefits of barefoot running with the protection and support of traditional running shoes. Today, many of these features remain integral in modern running shoe design, marking a lasting legacy of the barefoot running movement.

So in the end, while the barefoot running hysteria of 2010 may have been a short-lived trend, it sparked crucial conversations about running health and led to significant advancements in running footwear. Though no longer in the limelight, its impact continues to influence how we run and think about our running gear.